This is my first post on any forum on this website. I am astounded at the quality of work and talent that has been displayed in the various categories. Some of the images are stunning, and the information on techniques and equipment should prove extremely useful. By way of introduction, I am an entomologist and tropical biologist who has long been interested in photography for use in educational applications. My favorite subject is insects but I am writing for input about photomicroscopy. I have limited photomiscroscopy experience, having mostly done macrophotography in a studio (tabletop) settings.

I am looking for suggestions on a camera-microscope-photomicroscopy setup. My subject matter will primarily be commercially prepared and stained microscope slides such as students use in biology classes. I would like to be able to produce clear and instructive photos of subjects ranging from stages of mitosis and cell division at the high-magnification end on up to things like diatoms, the vascular bundles of plants, the spores of fungi, amoeba, hydra, etc.

Camera: I am leaning towards a Canon Digital Rebel or perhaps the next higher level Canon DSLR camera because so many colleagues in different disciplines have produced truly wonderful results with these cameras. And after my photomicroscopy work, I will probably shoot insects, plants, fungi more than anything else.

Microscope: I am wide open here, but with the wish to keep things as economical as possible while maintaining quality results. I thought that a microscope was essential, but have read that some of this site's members use setups consisting of a bellows with a microscope objective at the end. This too could be a possibility, but I am not a 'handy' person that can turn out items from a tool shop. We can assume that I will be buying and not making equipment, unless it is extremely simple to make.

Stacking: It is viewing stacked images that has really rekindled my interest in photography. I intend to use this technique in improving the quality and focus of my photomicrographs, so this is a consideration. Which stacking programs members have found easiest to use with microscopic subject matter.

Books & Articles: I have only just started going through the threads on this website, and I could spend days of enjoyable reading and image viewing. But given my goals, other members might be able to suggest the core articles that discuss the above subjects that would be the most useful. I have some old Kodak booklets that provide a good basis for understanding photomicroscopy and the physics behind it. But there must be recent publications that address the newer microscopes and the new breed of digital cameras that are now available?

Thanks to one and all for your patience. Please feel free to respond to any aspect of this post with your own experience and suggestions or direction to a link or article or previous post that would be helpful. My subsequent posts will be much shorter and specific.

Jim (JLCASTNER@AOL.COM)

Photomicroscopy Equipment Selection

Moderators: rjlittlefield, ChrisR, Chris S., Pau

-

James L. Castner

- Posts: 2

- Joined: Thu Mar 11, 2010 3:30 pm

- Location: Archer (Gainesville), Florida

Photomicroscopy Equipment Selection

Jim Castner

- rjlittlefield

- Site Admin

- Posts: 23626

- Joined: Tue Aug 01, 2006 8:34 am

- Location: Richland, Washington State, USA

- Contact:

Jim, welcome aboard!

Thanks for the detailed explanation of what you're interested in and what your constraints are. Please do not be concerned about writing postings that are too long for us. We can afford to read a lot more than you can afford to write.

To start answering your questions, let me quickly review the most important bits of theory.

The resolution of any lens system is ultimately limited by its aperture, in particular by how wide a cone of light is accepted from each point on the subject. A wider cone is required to resolve finer detail. This is because of diffraction. If you want to read more about that process, try HERE.

Up to a magnification of 5X or so (measured from subject to sensor on a typical DSLR), ordinary macro lenses have a wide enough aperture that you can resolve detail near the level of individual pixels. Since modern DSLRs have around 4000 pixels across the frame, this will make very sharp prints up to 10x15 or so. If your end use is for a textbook or for web presentation, then your resolution requirements are lower, and you can go to significantly higher magnifications using the same optics.

Beyond about 5X, ordinary macro lenses do not have a wide enough aperture to resolve all the detail that the sensor could capture. When you get to this point, you must switch to using different optics that are optimized to give very high resolution over a small field, using a wide aperture. Those are microscope objectives.

It turns out that there are some wrinkles in using microscope objectives.

In normal use, a microscope objective is always paired with an eyepiece. The usual description says that the objective creates a magnified intermediate image, which is further magnified by the eyepiece. You might imagine that the goal of objective designers is to create the best intermediate image possible, but that's not quite right. Actually the goal of microscope designers is to create the best final image possible. The intermediate image by itself is of no interest to most users of a microscope. Because of some subtle aspects of lens design, it turns out to be easier to create a high quality final image by only partially correcting aberrations in the objective, then finishing the correction in the eyepiece. Thus, with most objectives, the intermediate image is somewhat imperfect, typically having some field curvature and chromatic aberration that do not appear in the final image.

In some sense, then, the most reliable method for getting a good picture through a microscope objective is to use that objective with its matching eyepiece, and point a camera through the combination. This is called an "afocal" setup.

But then there's another wrinkle. A microscope eyepiece is designed to work with a human eye. Fundamentally, that means it's designed to mate nicely with an optical system whose entrance pupil is only a few mm behind the place where the eyepiece can be physically placed.

That creates a problem with many cameras, because their lens's entrance pupils are much farther than a few mm behind the first surface. (The entrance pupil is just where the aperture appears to be. Stop down the lens and look in the front to see where that is.) When the entrance pupil is too far back, the eyepiece and the camera lens are mismatched. Depending on how bad the mismatch is, plus some details of lens design that it's difficult to know about, you can get vignetting, image degradations such as reduced resolution and chromatic aberration, or both.

It should be obvious at this point that there are a lot of things that can go wrong. In general, picking up an arbitrary camera and pointing it down the eyepiece of a microscope will not work very well. So what to do, what do to?

One approach is to do away with the camera lens and use what's called a "projection eyepiece" that is designed to intercept the intermediate image formed by the microscope objective near the end of the eyepiece tube and relay it onto the camera's sensor, which of course is mounted somewhat farther back. If the projection eyepiece is properly matched to the objectives, this approach gives superb results. Otherwise it doesn't.

Another approach is to do away with both the camera lens and the eyepiece, and let the objective form its image directly on the camera's sensor. Through fortunate coincidence, the sensor size of a 1.6-crop-factor DSLR is pretty close to the size of an eyepiece field, which means there's a good match between the size of high quality image created by the objective, and the size of the sensor that's going to capture that image.

But there is still that little issue that with many objectives, the intermediate image (now the final image in this configuration) will have some aberrations. Curvature of field is no big deal if you are stacking, but chromatic aberration is definitely an issue. Even if you remove the obvious color fringes in post-processing, you're still left with some loss of resolution away from center because the lens has slightly different magnifications at different wavelengths within each band (R,G,B).

So, the trick to making this approach work well is to choose an objective that is well corrected all by itself. Such lenses are no longer made (as far as I know, and I would love to be corrected on this point!), but they are still available used if you're willing to wait a little while.

When you read in the forums about somebody using a microscope objective on bellows, what you're usually hearing about is one of the Nikon "CF" objectives (think "color free") that was specifically designed by Nikon to create an aberration-free image all by itself. These are wonderful creations. (I'll say no more, lest I drive the price up even higher.)

A word of caution, though. If you do decide to go this route (objective by itself), then it is a Very Good Idea to check specifically with our membership before buying any particular lens. There are many other lenses that do not work so well, but have very similar markings.

Getting back to the "what to do?" question, a third approach is to use an objective with its matched eyepiece, and be careful about choosing and configuring a camera to shoot through the eyepiece, thus using an afocal setup. There are a couple of ways to go here too. (Sigh...too many options...)

One approach (3a?) is to select a camera whose lens is reasonably similar to a human eye. Some compact digitals come equipped with built-in lenses that have their entrance pupils pretty close to the front. Such a camera will mate nicely with "high eyepoint" eyepieces that are designed for people who wear glasses. Unfortunately, the entrance pupil location is never part of the specification for these cameras, so unless you have the camera in hand or can get exactly the same model as somebody else who says its OK, what you get may not be what you expect.

A final approach (3b?) is to use an interchangeable lens camera and specifically choose a lens that will play nicely with the scope's eyepiece. The zoom lenses that typically come in camera kits are not likely to work well. Their entrance pupils are way too far back. However, it turns out that fairly short fixed-length "prime" lenses like the ones that came on old film SLRs are really not too far away from ideal.

Given your situation, and having now spent quite a bit of time thinking about this, I'm inclined to think that this last approach may be the best way for you to go.

Here is a setup that I put together this afternoon to check out the concept.

What you're looking at here consists of these components:

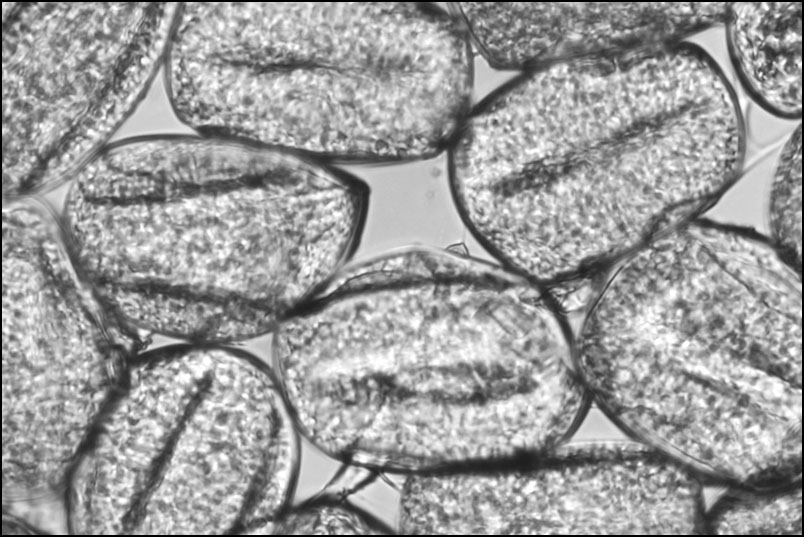

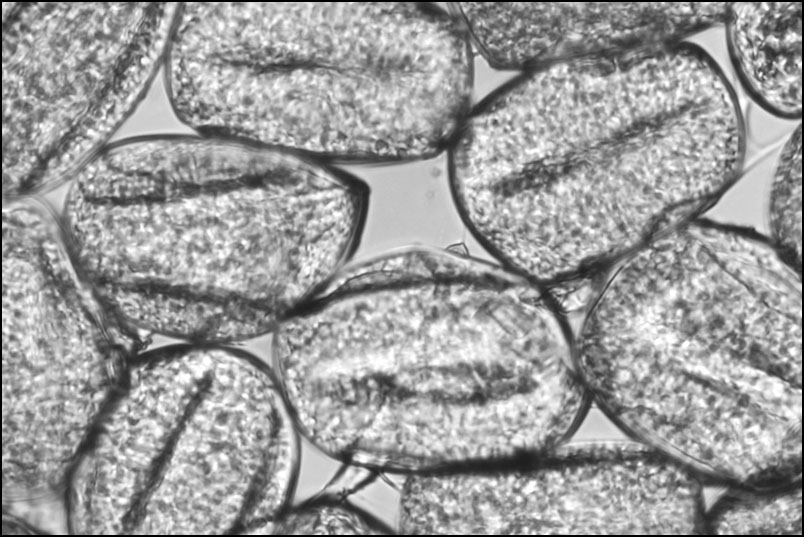

Here is the full frame (single shot, no stacking):

Here is a crop from the center of the frame, to show how much detail is available in the image. This has been resized to 50% in Photoshop, illustrating that the camera has significantly more resolution than was actually needed to capture all the detail resolved by the optics.

The above images have been converted to gray-scale because this type of pollen introduces prismatic colors that are pretty distracting.

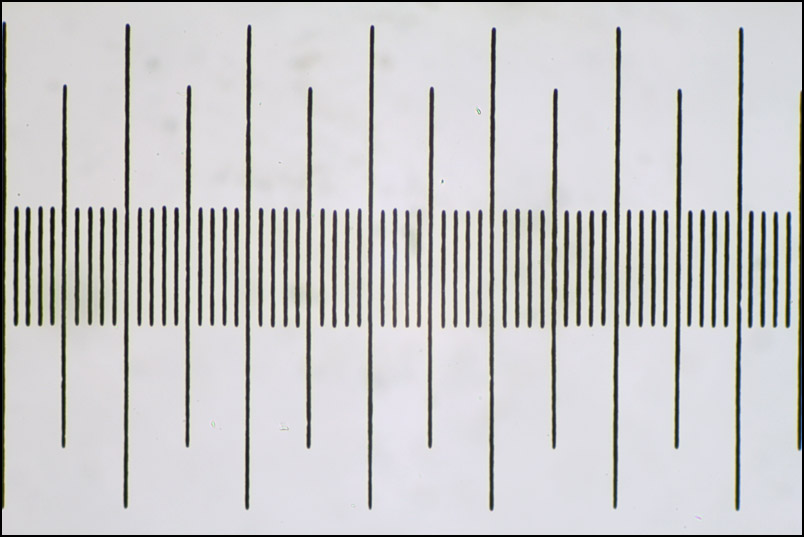

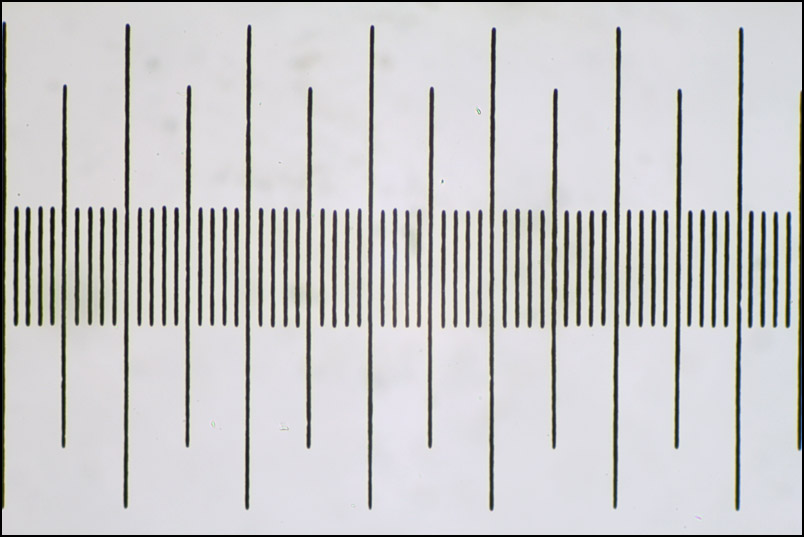

But here is a full-color full frame image of a stage micrometer. No processing except for color balance and resize. I'm pretty pleased with the absence of color fringes in this image.

The nice thing about this approach is that while it's undoubtedly not ideal, I can't think of anything that's likely to go very badly wrong.

This leaves open the question of what brand and model of scope you want.

The standard recommendation among the Yahoo Microscope group is to buy a used major-brand scope. I think that's a good recommendation if you can get together with a reputable dealer in used scopes who will walk you through options and issues and guarantee that the scope is OK. Buying used off eBay is pretty risky because there's so much that can go subtly wrong with scopes.

The other approach that makes sense (to me, but others may disagree), is to buy a new Pacific Rim scope, something like THIS ONE at Amscope. Their sales pitch has a gob of puffery in it, but the fact remains that you can get reasonable optics with darkfield designed in, a trinocular model with simultaneous view-and-photograph, and what looks like 30 mm of fine focus travel (check to be sure!) with a calibrated tick of 0.002 mm, all for about half the price of your camera. You're not going to get the same quality images that Charles Krebs does with his superb optics and illumination systems, but for the goals you've listed, it seems like a pretty low-risk approach.

One more thing, about the camera. What you probably want for photomicroscopy is one of the Canons that supports Live View and has an "electronic first shutter curtain". This has been discussed in the forum, but I would have to look up the references. Basically this feature is the ultimate in vibration avoidance. The mirror is locked up, the mechanical shutter is locked open, and the exposure is begun electronically -- no vibration at all. At the very end of the exposure, there is a bit of vibration when the shutter mechanically closes, but by this time it is too late to affect sharpness very much. When you are working with solid mounted slides, vibration is not so much of an issue. But you are likely to work your way into liquid mounts -- live protozoa, for example -- and for those the absence of physical vibration is a godsend. (It's actually pretty helpful a lot of the time. My T1i has the feature, and I use it routinely even in situations where I don't need Live View for any other reason.)

Regarding books, I suggest D. J. Jackson's several titles, available at http://www.lulu.com/microscopy. The wordsmithing is a bit rough, but I've found the information to be first rate. Nikon's website at http://microscopyu.com/ is also excellent, and they have a lot of tutorials.

This is enough for now. I will be interested to hear other people's suggestions.

Thank you for prompting me to think about photomicroscopy from a different viewpoint. (What would I do if I were apartment-bound, starting from scratch with no tools?) It has been at least a couple of years since I seriously considered shooting through an eyepiece with a DSLR. When I tried it before, it seemed prone to several ills. With a couple of years' better understanding, the picture is different. Funny how that works.

--Rik

Edited Mar 14, 2010 to add footnote: The objective I used here is nominally 20X, but is designed for use on a 210 mm tube. I was accidentally using it on a 160 mm tube. This results in reduced magnification, about 15X to the intermediate image. The image quality held up pretty well, considering the error.

Edited Dec 19, 2010, to clarify terminology.

Thanks for the detailed explanation of what you're interested in and what your constraints are. Please do not be concerned about writing postings that are too long for us. We can afford to read a lot more than you can afford to write.

To start answering your questions, let me quickly review the most important bits of theory.

The resolution of any lens system is ultimately limited by its aperture, in particular by how wide a cone of light is accepted from each point on the subject. A wider cone is required to resolve finer detail. This is because of diffraction. If you want to read more about that process, try HERE.

Up to a magnification of 5X or so (measured from subject to sensor on a typical DSLR), ordinary macro lenses have a wide enough aperture that you can resolve detail near the level of individual pixels. Since modern DSLRs have around 4000 pixels across the frame, this will make very sharp prints up to 10x15 or so. If your end use is for a textbook or for web presentation, then your resolution requirements are lower, and you can go to significantly higher magnifications using the same optics.

Beyond about 5X, ordinary macro lenses do not have a wide enough aperture to resolve all the detail that the sensor could capture. When you get to this point, you must switch to using different optics that are optimized to give very high resolution over a small field, using a wide aperture. Those are microscope objectives.

It turns out that there are some wrinkles in using microscope objectives.

In normal use, a microscope objective is always paired with an eyepiece. The usual description says that the objective creates a magnified intermediate image, which is further magnified by the eyepiece. You might imagine that the goal of objective designers is to create the best intermediate image possible, but that's not quite right. Actually the goal of microscope designers is to create the best final image possible. The intermediate image by itself is of no interest to most users of a microscope. Because of some subtle aspects of lens design, it turns out to be easier to create a high quality final image by only partially correcting aberrations in the objective, then finishing the correction in the eyepiece. Thus, with most objectives, the intermediate image is somewhat imperfect, typically having some field curvature and chromatic aberration that do not appear in the final image.

In some sense, then, the most reliable method for getting a good picture through a microscope objective is to use that objective with its matching eyepiece, and point a camera through the combination. This is called an "afocal" setup.

But then there's another wrinkle. A microscope eyepiece is designed to work with a human eye. Fundamentally, that means it's designed to mate nicely with an optical system whose entrance pupil is only a few mm behind the place where the eyepiece can be physically placed.

That creates a problem with many cameras, because their lens's entrance pupils are much farther than a few mm behind the first surface. (The entrance pupil is just where the aperture appears to be. Stop down the lens and look in the front to see where that is.) When the entrance pupil is too far back, the eyepiece and the camera lens are mismatched. Depending on how bad the mismatch is, plus some details of lens design that it's difficult to know about, you can get vignetting, image degradations such as reduced resolution and chromatic aberration, or both.

It should be obvious at this point that there are a lot of things that can go wrong. In general, picking up an arbitrary camera and pointing it down the eyepiece of a microscope will not work very well. So what to do, what do to?

One approach is to do away with the camera lens and use what's called a "projection eyepiece" that is designed to intercept the intermediate image formed by the microscope objective near the end of the eyepiece tube and relay it onto the camera's sensor, which of course is mounted somewhat farther back. If the projection eyepiece is properly matched to the objectives, this approach gives superb results. Otherwise it doesn't.

Another approach is to do away with both the camera lens and the eyepiece, and let the objective form its image directly on the camera's sensor. Through fortunate coincidence, the sensor size of a 1.6-crop-factor DSLR is pretty close to the size of an eyepiece field, which means there's a good match between the size of high quality image created by the objective, and the size of the sensor that's going to capture that image.

But there is still that little issue that with many objectives, the intermediate image (now the final image in this configuration) will have some aberrations. Curvature of field is no big deal if you are stacking, but chromatic aberration is definitely an issue. Even if you remove the obvious color fringes in post-processing, you're still left with some loss of resolution away from center because the lens has slightly different magnifications at different wavelengths within each band (R,G,B).

So, the trick to making this approach work well is to choose an objective that is well corrected all by itself. Such lenses are no longer made (as far as I know, and I would love to be corrected on this point!), but they are still available used if you're willing to wait a little while.

When you read in the forums about somebody using a microscope objective on bellows, what you're usually hearing about is one of the Nikon "CF" objectives (think "color free") that was specifically designed by Nikon to create an aberration-free image all by itself. These are wonderful creations. (I'll say no more, lest I drive the price up even higher.)

A word of caution, though. If you do decide to go this route (objective by itself), then it is a Very Good Idea to check specifically with our membership before buying any particular lens. There are many other lenses that do not work so well, but have very similar markings.

Getting back to the "what to do?" question, a third approach is to use an objective with its matched eyepiece, and be careful about choosing and configuring a camera to shoot through the eyepiece, thus using an afocal setup. There are a couple of ways to go here too. (Sigh...too many options...)

One approach (3a?) is to select a camera whose lens is reasonably similar to a human eye. Some compact digitals come equipped with built-in lenses that have their entrance pupils pretty close to the front. Such a camera will mate nicely with "high eyepoint" eyepieces that are designed for people who wear glasses. Unfortunately, the entrance pupil location is never part of the specification for these cameras, so unless you have the camera in hand or can get exactly the same model as somebody else who says its OK, what you get may not be what you expect.

A final approach (3b?) is to use an interchangeable lens camera and specifically choose a lens that will play nicely with the scope's eyepiece. The zoom lenses that typically come in camera kits are not likely to work well. Their entrance pupils are way too far back. However, it turns out that fairly short fixed-length "prime" lenses like the ones that came on old film SLRs are really not too far away from ideal.

Given your situation, and having now spent quite a bit of time thinking about this, I'm inclined to think that this last approach may be the best way for you to go.

Here is a setup that I put together this afternoon to check out the concept.

What you're looking at here consists of these components:

- microscope, unmodified.

- Orion SteadyPix camera mount.

- short piece of PVC pipe, split, serving as eyepiece tube size adapter.

- Canon T1i camera.

- lens mount adapter, M42-to-EOS.

- 55mm f/1.8 lens, circa 1966, salvaged from an old Pentax screw-mount camera.

Here is the full frame (single shot, no stacking):

Here is a crop from the center of the frame, to show how much detail is available in the image. This has been resized to 50% in Photoshop, illustrating that the camera has significantly more resolution than was actually needed to capture all the detail resolved by the optics.

The above images have been converted to gray-scale because this type of pollen introduces prismatic colors that are pretty distracting.

But here is a full-color full frame image of a stage micrometer. No processing except for color balance and resize. I'm pretty pleased with the absence of color fringes in this image.

The nice thing about this approach is that while it's undoubtedly not ideal, I can't think of anything that's likely to go very badly wrong.

This leaves open the question of what brand and model of scope you want.

The standard recommendation among the Yahoo Microscope group is to buy a used major-brand scope. I think that's a good recommendation if you can get together with a reputable dealer in used scopes who will walk you through options and issues and guarantee that the scope is OK. Buying used off eBay is pretty risky because there's so much that can go subtly wrong with scopes.

The other approach that makes sense (to me, but others may disagree), is to buy a new Pacific Rim scope, something like THIS ONE at Amscope. Their sales pitch has a gob of puffery in it, but the fact remains that you can get reasonable optics with darkfield designed in, a trinocular model with simultaneous view-and-photograph, and what looks like 30 mm of fine focus travel (check to be sure!) with a calibrated tick of 0.002 mm, all for about half the price of your camera. You're not going to get the same quality images that Charles Krebs does with his superb optics and illumination systems, but for the goals you've listed, it seems like a pretty low-risk approach.

One more thing, about the camera. What you probably want for photomicroscopy is one of the Canons that supports Live View and has an "electronic first shutter curtain". This has been discussed in the forum, but I would have to look up the references. Basically this feature is the ultimate in vibration avoidance. The mirror is locked up, the mechanical shutter is locked open, and the exposure is begun electronically -- no vibration at all. At the very end of the exposure, there is a bit of vibration when the shutter mechanically closes, but by this time it is too late to affect sharpness very much. When you are working with solid mounted slides, vibration is not so much of an issue. But you are likely to work your way into liquid mounts -- live protozoa, for example -- and for those the absence of physical vibration is a godsend. (It's actually pretty helpful a lot of the time. My T1i has the feature, and I use it routinely even in situations where I don't need Live View for any other reason.)

Regarding books, I suggest D. J. Jackson's several titles, available at http://www.lulu.com/microscopy. The wordsmithing is a bit rough, but I've found the information to be first rate. Nikon's website at http://microscopyu.com/ is also excellent, and they have a lot of tutorials.

This is enough for now. I will be interested to hear other people's suggestions.

Thank you for prompting me to think about photomicroscopy from a different viewpoint. (What would I do if I were apartment-bound, starting from scratch with no tools?) It has been at least a couple of years since I seriously considered shooting through an eyepiece with a DSLR. When I tried it before, it seemed prone to several ills. With a couple of years' better understanding, the picture is different. Funny how that works.

--Rik

Edited Mar 14, 2010 to add footnote: The objective I used here is nominally 20X, but is designed for use on a 210 mm tube. I was accidentally using it on a 160 mm tube. This results in reduced magnification, about 15X to the intermediate image. The image quality held up pretty well, considering the error.

Edited Dec 19, 2010, to clarify terminology.

Last edited by rjlittlefield on Sun Dec 19, 2010 1:18 pm, edited 2 times in total.

-

James L. Castner

- Posts: 2

- Joined: Thu Mar 11, 2010 3:30 pm

- Location: Archer (Gainesville), Florida

Thanks!

Rik, thanks for your thoughtful reply and useful information. In the next couple of weeks I shall try to read some of the articles and posts that are appropriate. Then I can ask some more pointed questions.

Michael, thanks for the kind words. For the first five years that I did macro work I used a Nikkormat EL camera with a 55mm macro lens and a single extension ring that allowed me to get 1:1 magnification. To this day I have never liked any setup better for the versatility of shooting macro or portraits or scenics. The last camera I used regularly for close-up work was the Olympus OM4T with a 50mm macro lens and a twin-flash setup that screwed onto the end of the lens. I'll be interested to see how you make out with your work with lichens and mosses, as eventually I will be shooting such organisms as well. Do you have the book LICHENS by Irwin Brodo et al.? Some great photos in there. It might be worth trying to find out what techniques they used? Same thing with the book MOSSES AND OTHER BRYOPHYTES by Bill and Nancy Malcolm. Good luck!

Jim

Michael, thanks for the kind words. For the first five years that I did macro work I used a Nikkormat EL camera with a 55mm macro lens and a single extension ring that allowed me to get 1:1 magnification. To this day I have never liked any setup better for the versatility of shooting macro or portraits or scenics. The last camera I used regularly for close-up work was the Olympus OM4T with a 50mm macro lens and a twin-flash setup that screwed onto the end of the lens. I'll be interested to see how you make out with your work with lichens and mosses, as eventually I will be shooting such organisms as well. Do you have the book LICHENS by Irwin Brodo et al.? Some great photos in there. It might be worth trying to find out what techniques they used? Same thing with the book MOSSES AND OTHER BRYOPHYTES by Bill and Nancy Malcolm. Good luck!

Jim

Jim Castner

- rjlittlefield

- Site Admin

- Posts: 23626

- Joined: Tue Aug 01, 2006 8:34 am

- Location: Richland, Washington State, USA

- Contact:

Jim, you're very welcome.

About photomicroscopy, it's worth mentioning that there are now high resolution USB cameras that come preconfigured with optics that make them act like eyepieces. See for example the collection HERE. These cameras will not provide the same levels of fine gradation and low noise that you can get with a DSLR, and I am concerned they may have little or no ability to work with flash. But they have the great advantage of coming preconfigured to do a good job with no fiddling. When I answered earlier, I had implicitly assumed that you would be wanting to do other things with your camera too, in which case a DSLR is far more flexible. But if you can afford a separate camera for just photomicroscopy, you should take a very close look at USB eyepiece cameras.

--Rik

About photomicroscopy, it's worth mentioning that there are now high resolution USB cameras that come preconfigured with optics that make them act like eyepieces. See for example the collection HERE. These cameras will not provide the same levels of fine gradation and low noise that you can get with a DSLR, and I am concerned they may have little or no ability to work with flash. But they have the great advantage of coming preconfigured to do a good job with no fiddling. When I answered earlier, I had implicitly assumed that you would be wanting to do other things with your camera too, in which case a DSLR is far more flexible. But if you can afford a separate camera for just photomicroscopy, you should take a very close look at USB eyepiece cameras.

--Rik